Tenure policies have been the center of a great debate in discussions pertaining to contingent workforce program management best practices for quite some time. And legitimate arguments exist both for and against establishing a tenure policy in an organization’s CW program business engagement rules.

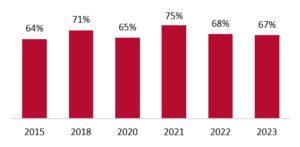

According to a recent SIA survey of contingent workforce management professionals, 67% of enterprise programs impose terms limits of some form. Tenure policy usage trends have risen and fallen around a small range over recent years, peaking in 2021 at 75% as the pandemic led companies to implement assignment limits on workers at a greater rate. However, uncertainty has waned since that time, which could explain the drop in the use of assignment limits to 68% in 2022 and 67% in 2023 (see accompanying chart). The most common assignment limits reported by SIA survey respondents are 18 to 23 months and 24-plus months, combining for 71% of the responses, with only 6% having a shorter assignment length limit policy of six to 11 months.

Percent of buyers with assignment limits, 2023

Source: Workforce Solutions Buyer Survey 2023

Tenure policies can have a legitimate role in the ongoing management of contingent workforce talent engagements, such as setting a point in time that engagement managers need to review the use of a specific CW talent in their business operations.

Reasons for establishing contingent talent assignment length limits can include:

- Executing the periodic business operational review of CW talent service usage;

- Preventing co-employment risk (in spite of known limited effectiveness);

- Enforcing talent retention/conversion;

- Protecting business critical talent and knowledge;

- Capturing cost-effective reassignment opportunities for proven talent skill sets; and

- Enforcing and capturing cost savings opportunities for longer-term assignments.

It is important to note tenure lengths are a very visible factor in most core government employee compliance tests in the marketplace. For example, the Department of Labor recently announced a final rule on independent contractor classification under the Fair Labor Standards Act which includes a factor pertaining to assignment length. The panoptic Darden Test includes a factor pertaining to assignment length.

While SIA’s research indicates that a significant number of CW programs do have contingent workforce engagement assignment length limits, too many of these are ineffectively installed to mitigate co-employment risks and/or to slay co-employment ghosts. More than a third of buyer respondents to SIA’s recent survey have elected not to have an assignment length limits policy. What do those buyer respondents know about tenure policies that those who have such a policy do not?

Here are some reasons for not establishing contingent talent assignment length limits:

- Tenure limits are not a major factor in courts’ co-employment rulings and thus have limited impact on mitigating co-employment risks.

- Tenure limits are difficult to enforce.

- Tenure limits potentially burden the CW engagement service with non-value-added bureaucracy.

- Tenure limits can lead to increased recruiting and training costs because of unnecessary forced turnover.

- 70% of engagements are fairly long-term anyway.

- Some engaged CW talent have hard-to-find skills, and replacing them due to term limits would be a challenge.

- Contingent talent are increasingly important in the current tight labor market.

Assignment limits can vary by occupation; some skill sets are more difficult to find/replace, higher-paying roles (like IT and legal) will often have longer assignments due to the nature of the work and the intellectual property they hold, and certain occupations with a high turnover rate and/or short assignments are less likely to set tenure limits. For example, a majority of healthcare and education organizations have no assignment limits in place for CW roles.

In many cases, the requirement for a contingent worker is temporary, associated with a specific business need with a defined beginning and end timeframe. But in a growing number of circumstances, budgetary and headcount constraints are making these business requirements longer term in nature and/or a permanent manner in which the business is conducted. It is not surprising to see some CW engagement lengths range more than five years for specific business needs, such as for long-term temporary roles.

At the end of day, tenure policies do provide value in the execution of an organization’s strategic workforce plan. A tenure policy can be used to force an employment status review of contingent worker talent. It’s been noted as “completing the try-and-buy” value of engaging a contingent worker. At some stated point in time, engagement managers need to evaluate why a specific contingent talent is not more fully integrated and secured in a full-time employment role within the organization.

It just seems logical that contingent talent who are successfully delivering highly valued skilled services should be systematically evaluated for a longer-term permanent role in the organization before their skill sets and knowledge are lost to other employers competing in the marketplace. Similar to the need to promote successful full-time talent as their value grows within an organization, contingents will take their careers elsewhere when those promotions do not emerge in a timely manner, resulting in painful turnover costs, damage to an employer’s brand and — possibly the most important — the loss of good talent that is hard to find.

Finally, perhaps a CW talent workforce evaluation policy needs to be established that does not drive specific assignment limits or forced turnover actions unless business needs and requirements are not being met; more importantly, it must focus on the competitive retention of the cost-effective skills and value being delivered.